The view from the lobby of the Marriott Marquis in Atlanta got me thinking about this film – specifically, the way it transports the viewer to another world. That’s an overused phrase, of course. All worthwhile science fiction films transport the viewer to another world… but not so many of them present that other world in such exquisite detail. I think of the way that Peter Jackson’s LORD OF THE RINGS films capture the encyclopedic minutiae of Tolkien’s Middle Earth, or the way that James Cameron’s AVATAR thoroughly immerses viewers in the 3D environment of Pandora. Ridley Scott’s BLADE RUNNER not only makes it possible to believe in Philip K. Dick’s dystopian future, but nearly impossible NOT to believe in it. Like the Replicants in the story who are built to be “more human than human,” the world of BLADE RUNNER often seems more real than reality.

I think that’s why the film made such a strong impression on me when I first saw it on home video. The visceral experience felt real enough to obsess about, and my friend Ben and I obsessed plenty. Back in the quaint days of Usenet, we used future technology to collect information about alternate versions of the film. The main debate on the Usenet boards: Was Deckard himself a Replicant? The “director’s cut,” released in 1992, fueled the debate. Ridley Scott provided no clear-cut answers, but that was all for the best. Mystery means that there are still more secrets to be discovered, and that’s what makes life (artificial or otherwise) interesting. When the soundtrack by Vangelis was finally released on CD in 1994, I promptly bought a copy and played it on repeat while I slept at night – hoping, I suppose, for dreams that were as wild and elaborate as BLADE RUNNER.

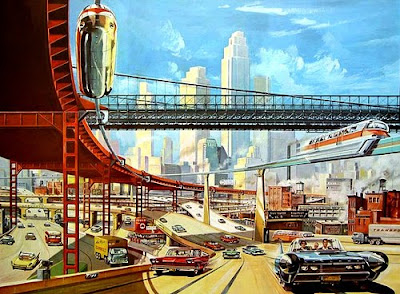

Ridley Scott once said, “To me, a film is like a seven-hundred layer cake… Every incident, every sound, every movement, every color, every set, prop or actor, is all part of the director’s overall orchestration of a film.” Scott’s process began with what he calls “pictorial layering,” as he imagined the post-nuclear dystopia of Philip K. Dick’s novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (The title “Blade Runner” actually came from an unrelated script by William Burroughs, and Scott’s film dispensed with the novelist’s idea that the ultimate status symbol, in the postapocalyptic future, was ownership of a live pet.) Scott‘s agenda was very specific: He sought the tone of Edward Hopper’s “Nighthawks” painting, the energy of Jean Giraud’s work for Heavy Metal, and the retro quality of Syd Mead’s Sentinel.

The tone of “Nighthawks” comes across in the opening sequence of the finished film. An eyeball reflects the desperate landscape of 2019 Los Angeles, a city of eternal night, lit only by neon and exhaust flames. Fans call it the “Hades landscape” (and would later see a facsimile of it in the cult hit THE CROW). We don’t know whose eye is watching this landscape, or if the watcher is human… and maybe that’s the point. Right away, there’s a certain coldness about Scott’s storytelling. It’s all about the object seen, not so much about the seer. Scott effectively disembodies us, as viewers, in order to draw us into a world where people are isolated and alienated.

Flying into Los Angeles in 2011 can fill a person with similar sensations. The greater L.A. area is so sprawling and so densely packed, yet so neatly divided into hundreds of smaller communities along invisible lines. Within most of those communities, there is even more division. Last week I wrote about a brief exchange between characters in the war film THE THIN RED LINE. One soldier asks, “Do you ever get lonely?” The other answers, “Only around people.” It’s astounding to think that, in a city of roughly four million people, anyone could ever get lonely. But I think it’s probably easier to get lonely in Los Angeles than in a small town. (In all fairness, it’s probably also easier in L.A. to distract yourself from that loneliness.) I’m likewise reminded of the scene in Michael Mann’s film HEAT, when Robert DeNiro looks out on the city from an apartment balcony above Sunset. Instead of seeing the light as human life, he sees “iridescent algae.” The woman he’s with astutely follows up with a (rhetorical) question: “Are you lonely?” In a city this size, it’s hard not to feel insignificant.

In a way, Philip K. Dick is asking the same question in his novel. His main character, Deckard, is becoming desensitized to human emotion. While hunting androids, he becomes an android himself, according to Dick’s definition. “In my mind,” the author says, “android is a metaphor for people who are physiologically human but behaving in a nonhuman way.” Deckard is a remorseful killer – like a World War II veteran sorting through the moral ambiguities postwar film noir, or a Vietnam veteran among soulless yuppies in Reagan’s America.

Screenwriter David Fancher says that he always intended BLADE RUNNER to be a rebuke of the “cruel politics” of Ronald Reagan, whose presidency marginalized the poor and promoted class conflict. With this idea in mind, Fancher offered his own take on the dynamic between Deckard and the Replicants: The “hero” became a cold-hearted enforcer while the “villains” became sympathetic. Producer Michael Deely went so far as to equate Deckard with “a heartless Nazi commandant” who falls in love with “his beautiful Jewish prisoner” (Rachael). To Scott, the Replicants were more than beautiful prisoners – they were super-humans, an evolutionary leap forward. The visuals of the film reflect a related sense of hope for a future which is frightening yet inspiring. I've always felt that the ultimate human emotion is awe, and BLADE RUNNER certainly conjures a sense of awe.

It has been remarked that Scott’s emphasis on visual storytelling, to say nothing of his apparent admiration for the purity of the Replicants, makes the film seem cold and clinical. On one level, BLADE RUNNER is a story about a man falling in love with an android. At the same time, that man is made to look contemptible by comparison to the androids. He’s slower, weaker, more bigoted, less ethical, and ultimately less interesting. It’s not hard to understand why Harrison Ford found himself at odds with Ridley Scott during the making of the film. BLADE RUNNER tramples his heroic Indiana Jones persona. It even tramples his anti-heroic Han Solo persona. Though Deckard is supposed to be the human at the center of the story, he sometimes seems like the least human character in the film. (Then again, to be fair, MANY of Ford’s subsequent roles have been even more emotionally vacant than Deckard… so I’m not inclined to place the blame entirely with Ridley Scott.)

In the theatrical cut, Ford has to deliver the following line of narration: “Sushi – that’s what my ex-wife called me. Cold fish.” It’s meant to be a self-effacing joke in the slightly misogynistic tradition of film noir detectives but it seems more like a filmmaker’s condemnation of his main character. Deckard IS a cold fish. Even when he puts the moves on Rachael, he’s so unnecessarily aggressive that he seems to hate himself for it. When he shoots Zhora in the back, he seems more dazed than remorseful.

By comparison, Rutger Hauer is all too human. He is Nietzsche’s superman, who willingly plays the role of God – killing his creator with his bare hands, but not without a sense of profound loss for this liberation. He knows that he has done “questionable things,” but he accepts responsibility, and with a sense of whimsy. The actor confides, “The best trick Ridley played with Roy and the other replicants was that he told us early on – the androids, that is, Daryl Hannah and Joanna Cassidy and Brion James and myself – to relax and be comfortable. To have fun and to make the replicants likable. And we did. That, I think, is their underlying appeal.” As a result, the Replicants – especially Hauer’s Roy Batty and Daryl Hannah’s occasionally childlike Pris – are truly more human than human. It is Batty who teaches the “hero” about ethics (“Not very sporting to fire on an unarmed opponent… Aren’t you the Good Man?) and the value of life.

Hauer’s partially improvised “tears in rain” speech remains the coup de grace of the film. This living creature with a heightened intelligence understands, in his final moments, what few humans are willing to acknowledge: All of the unique moments that we witness, in the particular way that we experience and understand them, will die with us. In essence, part of the world dies with us. Part of the world dies every day. Every second. The converse is also true. The world is constantly being reborn. That’s why Batty saves Deckard. In the process, he makes Deckard a better human being. It is an android who teaches the human to recognize the beauty of life.

That, says Ridley Scott, is the only worthwhile jumping-off point for a sequel (which, according to Hollywood rumor, is currently in the works): “If Deckard was the ‘piece de resistance’ of the replicant business – ‘more human than human,’ as Tyrell would say – with all the complexities suggested by that accomplishment, then a Nexus-7 would, by definition, have to be replication’s perfection. Physically, this would mean that the Tyrell Corporation would be prudent in having Deckard be of normal human strength but extended lifespan – resistance to disease, etc. Then, to round off their creation, the perfect Nexus-7 would have to be endowed with a conscience. Which would in turn suggest some kind of need for a faith. Spiritual need. Or a spiritual implant, in other words.”

[All quotes are taken from Paul M. Sammon’s remarkable book FUTURE NOIR: THE MAKING OF BLADE RUNNER. If you have any interest in the film, you owe it to yourself to check out this book.]

Excellent post for an extraordinary film (no matter which version one selects), Joe. I caught the original theatrical release when it first came out. Still, one of the most haunting pieces of cinema I ever watched on the big screen. Thanks for this.

ReplyDeleteThanks, Michael. I'm curious to know where you saw it on the big screen... I like to imagine it was at the Million Dollar Theater...

ReplyDeleteNevermind... Just found the answer:

ReplyDeletehttp://le0pard13.wordpress.com/2011/06/25/tmt-before-unicorn-dreams/

Joe,

ReplyDeleteOnce again, my apologies for being extremely late here.

I was excited to see another fine post, but knew I needed to find the time to read it and give it the proper look.

It's funny you mention that Blade Runner book. I have it on my shelf and I have yet to read it. Hopefully soon. I was busy finishing your fine book first.

I saw the film with my mother. I was young and I believe it was one of the first Rated R pictures I had seen along with Boorman's Excalibur. Blade Runner simply blew me away. It affected me in profound ways that resonate with my love for science fiction today through my own Musings site as you might imagine.

It affected me in the way The Thing Red Line affected me in a smaller way years later as you wrote in another terrific post.

Like you - I love the Vangelis score and the CD is one of my fave soundtracks. It took the longest time to finally see it replace the Philharmonic version that circulated forever. I kept yelling, WHERE IS THE REAL VANGELIS SOUNDTRACK? Someone finally heard me. : )

With regard to issues of class warfare I don't think I've heard it bandied about quite as much in my life as I have with the current administration. Every speech is about rich and poor and middle class lately. It's tiresome and divisive. Merely my opinion on my own political observations of late.

I truly enjoyed your observations particularly the second to last paragraph. That Tears In The Rain speech is a classic. It's simply beautiful. Poetry in film. You offer some lovely remarks on the film's major moment.

All the best,

sff

Thanks for your comments, Gordon! Just yesterday, I finished another relevant book -- an intellectual biography of Philip K. Dick called I AM ALIVE AND YOU ARE DEAD. (This one is also worth adding to your bookshelf!)

ReplyDeleteThe bio presents the sf writer as a visionary in the most ambitious sense of the word -- a prophet for a new religious age. According to biographer Emmanuel Carrere, one of Phil Dick's biggest crises followed the resignation of Tricky Dick Nixon. Supposedly he regarded Nixon as a LITERAL anti-Christ, and felt emotionally deflated when his nemesis fell from power. (I've heard the same thing about Hunter Thompson... but I don't think Thompson, even in his most drug-addled state, believed that he was LITERALLY on a mission from God...)

One wonders what Dick would have made of the current state of American politics, which seems to be getting closer and closer to the sf writer's dystopian fantasies...

That is interesting. Good question Joe.

ReplyDelete