Okay, confession time: I didn’t see BIG TROUBLE IN LITTLE

CHINA until 1997, more than a full decade after it was released in

theaters. I’m not really sure why. I had seen all of Carpenter’s early films on

video, and I lined up on opening night to see IN THE MOUTH OF MADNESS (1994),

VILLAGE OF THE DAMNED (1995), and ESCAPE FROM L.A. (1996) in the theater. But, somehow, BIG TROUBLE just didn’t come up

on my radar. Until my first weekend at

college.

It was the late August 1997.

I didn’t know anyone on campus. I

didn’t have a car, so I couldn’t leave campus.

I really had nowhere to go, except to the library or the campus movie

theater. I decided to check out the

theater, and saw that the inaugural movie of that particular season of

screenings was John Carpenter’s BIG TROUBLE IN LITTLE CHINA. As it turned out, I was a member of a very

small group of people (mostly other freshmen, I presume) who ditched the

start-of-semester parties to go to the movies.

And as soon as Jack Burton’s truck came barreling at the

screen—accompanied by the rockin’ blues of JC himself—I felt right at home.

I’ve written a lot over the years about movies as comfort

food. I’m not sure if that’s really what

this particular movie is for me, but I have a theory that that’s what it is for

John Carpenter. BIG TROUBLE isn’t really

like any other title in his canon. Oh

sure, you can make the easy comparison to ESCAPE FROM NEW YORK—because Kurt

Russell headlines both films, and there’s an undeniable commonality between the

heroes of both films. Snake Plissken and

Jack Burton are very different animals, but they’re both western-movie

caricatures (based on Clint Eastwood and John Wayne, respectively), and the

worlds they exist in are bold and brilliant fantasies. ESCAPE exists in an alternate-reality

America, a dystopian sci-fi realm. BIG

TROUBLE, on the other hand, exists in a surreal Chinese underworld, an exotic mythical

realm every bit as rich as the wild, wild West—if not moreso.

|

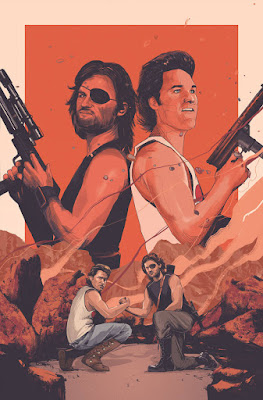

| Oliver Barrett cover art for the BIG TROUBLE IN LITTLE CHINA / ESCAPE FROM NEW YORK crossover comic |

I can only imagine what it must have been like to see this

seemingly idiosyncratic combination of swords, sorcery and slapstick on the

screen in an American theater in 1986.

By 1997, I’d already been exposed to Hong Kong action movies. This was still a few years before Quentin

Tarantino attempted something (tonally) similar with KILL BILL, but I was

certainly aware of Jackie Chan and John Woo.

I’d even seen A CHINESE GHOST STORY, an early film by producer Tsui Hark—although

I didn’t know what to make of it at the time.

American audiences in 1986—the hep ones, that is—had a smaller frame of

reference. Ditto John Carpenter, whose

list of influences for BIG TROUBLE is a spectacular triple feature of Asian

cinema classics:

The Shaw Brothers kung-fu epic FIVE FINGERS OF DEATH (1972). Carpenter remembers, “Back in 1973 in the

United States, there was a big deal over FIVE FINGERS OF DEATH, which was the

first martial arts movie that had made it to our shores. It was delightful. It wasn’t just that the kung fu was fu, there

was a sense of innocence to the Chinese cinema.

It was strange, yet bloody and violent and innocent at the time, plus with a ‘what is this exactly?’ vibe

about it.”

SHOGUN ASSASSIN (1980), a Japanese samurai TV series recut as

a grindhouse movie for American audiences.

Carpenter fans will recognize the anarchic spirit of this movie—as well

as the three super-villains in giant hats.

And, most importantly, Tsui Hark’s ZU: WARRIORS FROM THE

MAGIC MOUNTAIN (1983), which Carpenter himself has called “a real WIZARD OF OZ

kind of Chinese film” and “the Chinese STAR WARS.” This film, he says, was the biggest

inspiration for BIG TROUBLE, because “it permitted me to say, ‘Ok, we can do

anything here.’”

That “anything goes” spirit is the key to the success of

Carpenter’s film, and it’s what makes BIG TROUBLE so much fun. The filmmaker has said that the freewheeling atmosphere

came partly from his experience as a new father. The 1986 press kit quoted the director as

follows: “I think a lot of this has to do

with my relationship with my son, who is now two years old, and seeing the

world a little through his eyes. I am a

person with a lot of darkness in his view of the world. But through my son I can see a really

ridiculous, fun world, an enormous, wondrous world, and that’s a little bit of

what I wanted to get into this…. [also] I felt I’m getting older in my career,

I’m almost forty years old, and I’d better do something nuts while I can.” The cast, it seems, was just as willing to

“go nuts.” Kurt Russell, especially, has

a field day here—taking chances that perhaps no other leading man would have taken

in a big studio movie in 1986. From what I can tell from reading The Official Making of BIG TROUBLE IN LITTLE CHINA, everyone had fun making this movie, and their joie de vivre comes across on the screen. Asian

martial arts movies have never been my bag… but I love John Carpenter’s take on

the genre.

Unfortunately—if not unsurprisingly—the film didn’t catch on

with American moviegoers in the summer of 1986.

The big hits that year were TOP GUN, ALIENS, FERRIS BUELLER’S DAY OFF, KARATE

KID 2, STAND BY ME, CROCODILE DUNDEE, etc.

Carpenter’s film got lost in the shuffle—no thanks to a lousy marketing campaign

orchestrated by 20th Century Fox. The reception to the film was so

cold that the filmmaker vowed (as he had after his last big-budget failure, THE

THING) not to do anything like that

again. In this case, what he meant was

that he didn’t want to make any more epic-scale blockbusters for major

Hollywood studios; instead, he wanted to get back to making smaller, more

intimate pictures.

|

| This ad for BIG TROUBLE posed a question that contemporary viewers apparently didn't need an answer to. |

A year later, he struck a four-film deal with Alive

Films. His first project under that deal

was PRINCE OF DARKNESS, which—on the surface—couldn’t be more different from

BIG TROUBLE IN LITTLE CHINA. PRINCE OF

DARKNESS is a small, dark, brooding, claustrophobic, intensely-intellectual

horror movie. But it does have something

in common with BIG TROUBLE IN LITTLE CHINA.

The earlier film, like its primary inspiration ZU: WARRIORS, is rooted

in an elaborate Chinese cosmology of good and evil—and that cosmology may, in

turn, have inspired John Carpenter to develop his own elaborate cosmology for

PRINCE OF DARKNESS.

Here’s what the 1986 press kit had to say about the Chinese mythology

behind BIG TROUBLE: “According to this

mythology, perpetual life on earth is accorded not only to the forces of good,

but also to the demons of evil—those from Hell.

It isn’t certain how many Hells there were for the Chinese, but Hell was

ruled by an elaborate bureaucracy which meted out punishments to the evil

exactly calculated to match their crimes.

Chinese mythology is filled with such people as the Dragon King, the

Monkey God, the King of Dead, the Dark Warrior, the Green Dragon of the East

and hundreds more. To these, BIG TROUBLE

IN LITTLE CHINA adds Lo Pan, the epitome of evil, who’s been around for over

2000 years, looking for a green eyed maiden to free him from an ancient curse

and restore him to his physical body.”

In a similar fashion, PRINCE OF DARKNESS would be built upon

the bones of Christian theology and (more generally) Western religious dualism. To these elements, Carpenter would add his own

scientific approach to evil—creating a completely new type of horror movie for

the 1980s.

No comments:

Post a Comment