Saturday, February 04, 2012

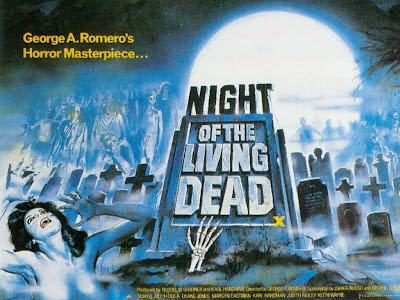

MOVIES MADE ME #38: NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD

This is my prologue to a series of essays I've written about the films of George A. Romero. I thought I'd post it in celebration of the director's birthday. I hope to see the entire series published later this year...

The first time I saw George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968) was in the early 1990s on home video. It was a cheap, public domain copy with abysmal sound and picture quality. Sometimes I wonder if my initial interest was partly due to the grittiness of that copy. I watched it on a small black and white TV, the way Ben (the main character in the film) watches the world collapsing on a small black and white TV. I was twelve or thirteen years old, and it wasn’t hard for me to suspend my disbelief and imagine that the everyday world no longer existed outside my own bedroom window. In a way, that scenario was utterly terrifying. In another way, it seemed like a potential blessing.

I must have watched Night of the Living Dead a dozen times before I moved on to the sequels, Dawn of the Dead (1978) and Day of the Dead (1985). Dawn was epic by comparison – revealing a civilization at the height of its struggle for survival; Day returned to the original vision, showcasing humanity in the throes of defeat. On the night I watched the third film, an ice storm swept through the small Virginia town where I grew up. It knocked out the power and buried our house. My parents and my younger brother gathered in the living room, and huddled in sleeping bags around the fireplace. After everyone else fell asleep, I sat listening to AM radio news on my Walkman until the batteries ran down. The storm kept us confined within the neighborhood for over a week, and all the while I kept wondering what it would be like if the snow never melted. My parents wouldn’t go back to work. My brother and I wouldn’t go back to school. A much smaller community would take shape, and we’d have to talk to each other and trust each other as never before. We’d undoubtedly come to appreciate each other more, because in such a small world there would be fewer distractions. Questions about life and death, meaning and morality would be discussed openly, because human life would be stripped down to its essence: not just survival but survival for a purpose. Part of me still yearns for such a fate... though, of course, it would be nice if that kind of world came without the zombies.

George Romero hopes that zombies can change the world for the better by forcing us to focus on what’s really important. Without that kind of immediate threat, we return to mundane habits. This truth is illustrated by the later films in Romero’s series – Dawn, Day and Land of the Dead (2004) – as well as the British satire Shaun of the Dead (2006). Herein lies the hidden meaning of Romero’s apocalypse: The force that really turns us into “zombies” is civilization. When we become too preoccupied with work, money, politics, news, weather and sports, we forget about intimacy and humanity. It’s no secret that Romero himself prefers the zombies to many of the humans in his films. The zombies may be uncivilized, but at least they’re not over-civilized.

When I had the chance to interview the director in 2008, I told him that his Dead films had exerted a profound influence on my life. He seemed genuinely surprised, and maybe even a bit concerned about my claim. How, he asked, could a cheap zombie movie made in 1968 have such an impact on someone who came of age in the 1990s? To Romero, Night of the Living Dead is inextricably linked with the zeitgeist of the late 1960s. “In my mind,” he told me, “most of the power it has relates to the time that it was made… and the anger of that time… and the disappointment of that time.” Since I didn’t personally experience 1960s America, obviously I can’t fully understand the film in that context. But something else he said made me realize that I experienced Night of the Living Dead in a different but equally powerful context. While explaining that his Dead films are really about the human characters and the ways they inevitably “screw up” their chance to start a new and better world, he said, “The zombies could be any natural disaster.”

I suddenly remembered that, in high school, I’d frequently had nightmares about natural disasters. In one particular dream, a hundred-foot-high tsunami descended on the hotel in Virginia Beach where my family was vacationing. That was the most familiar image of nature in revolt that my imagination could conjure. Had I grown up on the West Coast, I might have dreamed of an earthquake or a volcano. If I lived in Middle America, it might have been a tornado or an all-consuming dust storm. Such dreams reveal the fear of death at its most basic: We cannot escape nature. Death is as natural as life, and physical survival is a game that we all lose eventually. The only way to survive, I figured, was to assess what was really important in life, and then live with a clear purpose.

As a precocious teenager, I didn’t know how to talk about such things with friends and family. With the exception of a few late-night (often drug-induced) conversations, the ideas seemed too abstract for the world I was living in… and yet I couldn’t let them go. Neither could Romero. The filmmaker explains that this was his basis for Night of the Living Dead: “What would be a really earth-shattering thing that would be revolutionary and that people would refuse to ignore? The dead… stop… staying… dead.” Actually, it’s even more dramatic than that. Romero adds with a grin, “Oh and there’s one thing more… They like to eat living people!”

Happy birthday, George!

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Wonderful piece and celebration for George Romero's legendary film, Joe. Well done.

ReplyDelete